A Citizen’s Guide To Interest Rates

Why The Average Joe/Jane Should Understand What They Mean

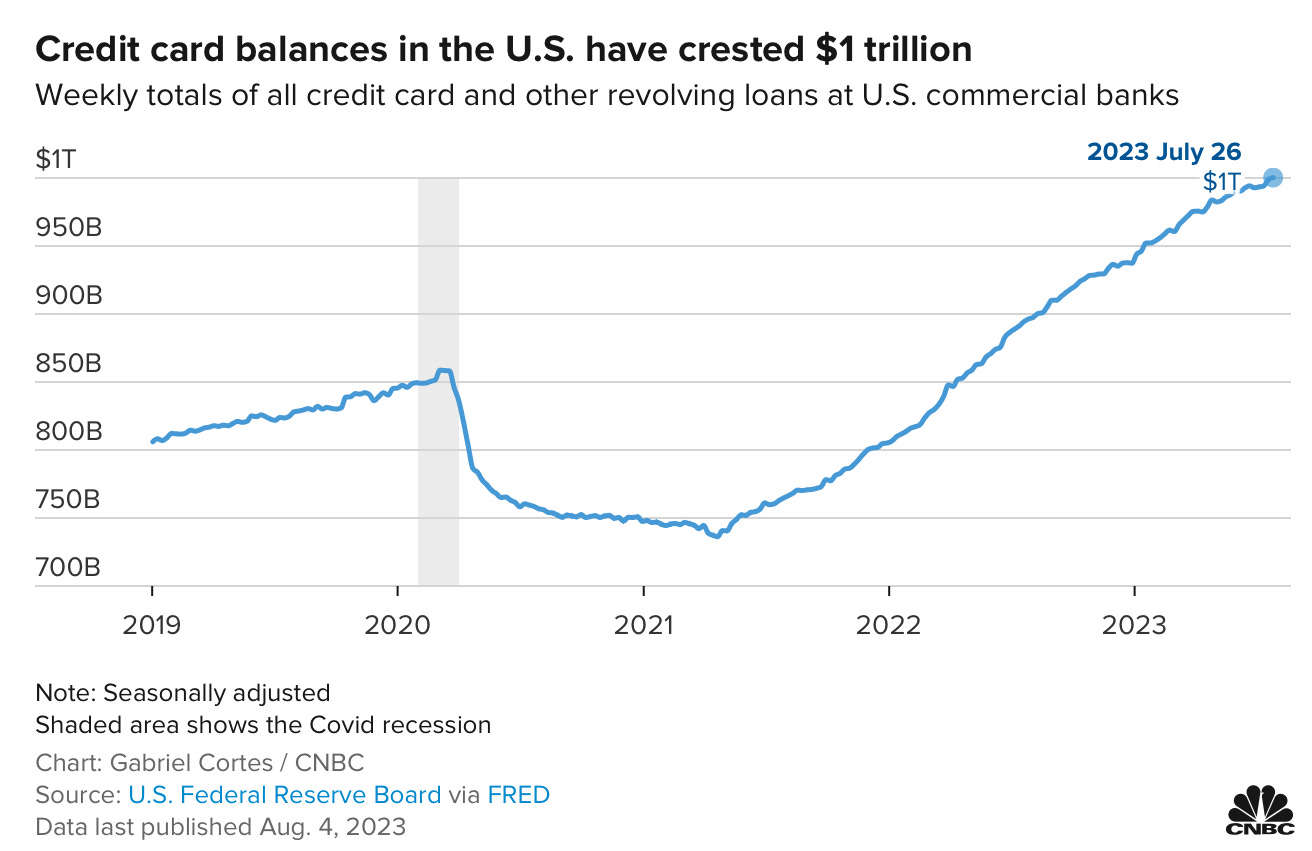

Credit card debt just hit one trillion dollars.

$1,000,000,000,0000. That’s a lot of zeros.

Let that sink in for a second.

What should shock you about this number is not the vastness of it, but the fact that people are willing to incur expenses at one of the highest interest rates to ever exist (compared to mortgages and car loans, for example).

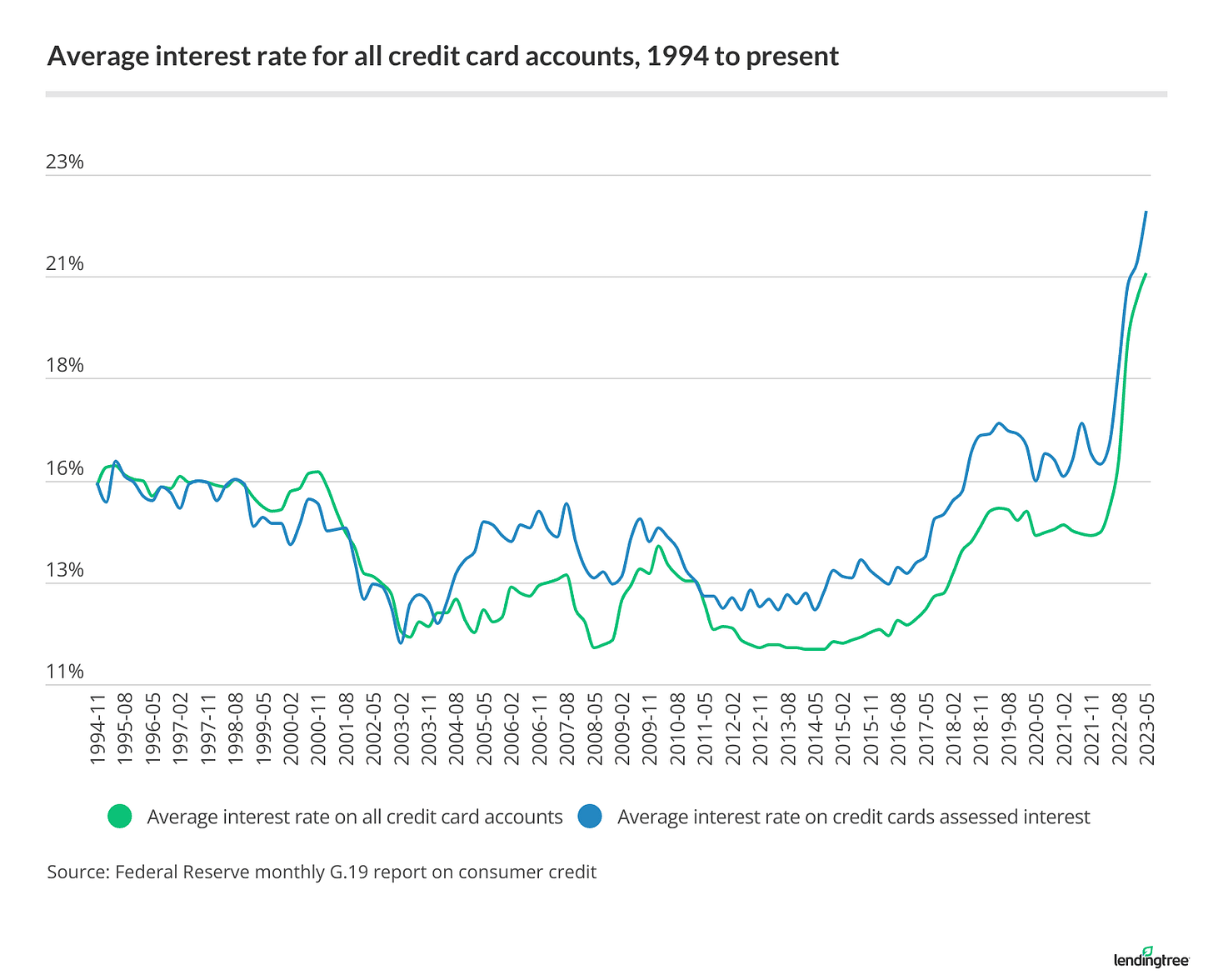

As of June 2023, the average interest rate on credit cards was passing a whopping 20%.

That means that for every dollar you borrow from the bank, you owe them 20 cents as a cost of borrowing.

For the bank, though, this 20% is a return for lending you that money. Keep this in mind as it becomes important a little later.

Why is this happening? Well …

When broader interest rates are low (which was the case since 2009), banks often lower lending standards. This means they might offer credit cards to riskier borrowers.

And, with the convenience of digital transactions, a consumerist culture, and easy access to credit, many consumers have found themselves accumulating high balances on their cards.

This combination of easy accessibility and high rates have led to this ballooning effect on debt.

However, I would argue that interest rates are much more important in dictating the behavior that led to this massive debt number.

And the whole point of this article is to try and unpack interest rates as much as possible. Because regular people like you and I need to get this right.

In order to do that, let’s go back in time.

Charging Interest Was A Sin?

Interest rates, as we know them today, go back to ancient civilizations. Merchants in Babylon, for example, extended credit and expected a return for the wait.

But in the more recent part of history, especially the one highly influenced by religion, charging interest was considered sinful. The term for it was ‘usury’. A practice frowned upon by Jews and Catholics.

But, as with everything, a few loopholes were found to this sinful practice.

Jews could not charge interest to fellow Jews, but it was allowed when lending money to non-Jews.

Catholics, like the Medicis, earned interest through fees or currency exchange rates — which were more related to business practices rather than lending — and allowed them to comply with church doctrines.

As you can see, interest has always been about earning a return on your money.

Whether it is because of you’re putting up with a time horizon or a specific risk.

Is it still a sin? I’ll let you answer that question on your own.

So, how does someone determine what that return should be?

How Murphy’s Law Determines Interest Rates

"Anything that can go wrong will go wrong."

Returns are all about compensating for risk.

The risks that come with placing your money on a given bet. From putting your money in a savings account to investing in the stock market or real estate.

A return rate is all about estimating the chances and consequences of something going wrong and placing a risk tolerance value on that opportunity.

In other words, how much do you want in return to put your money somewhere where everything might go to hell?

In the example above, the bank considers they should get a 20% return for lending money to risky borrowers through a credit card.

So, how do you get to that number?

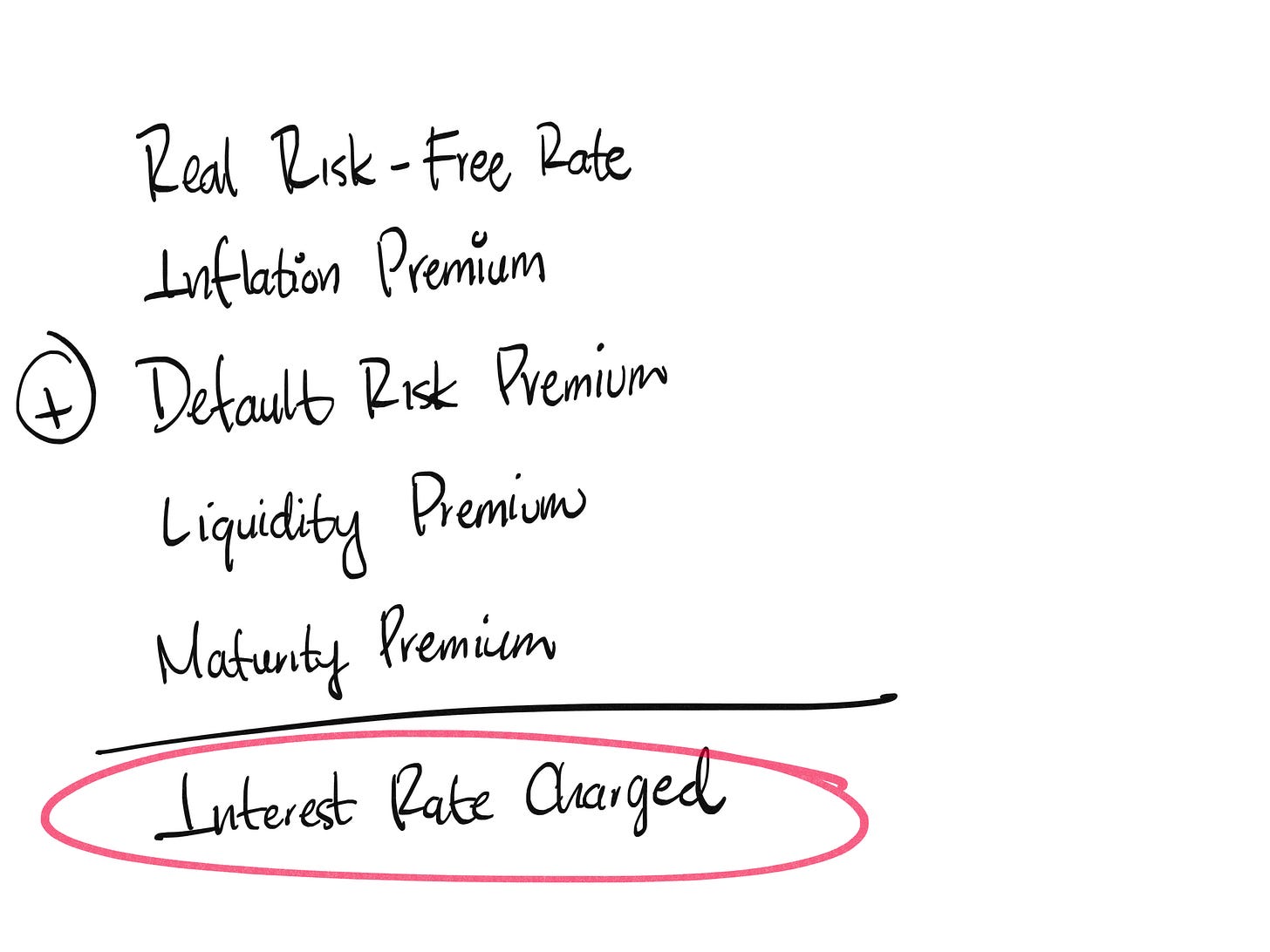

There are five main building blocks that make a return.

We’ll go through them now:

Real Risk-Free Rate: This one doesn’t exist. Full stop. It’s a theoretical rate of an investment that doesn’t carry any risk if no inflation is expected. But, there’s no such thing. Even the safest investment, like giving your momma a loan, has a small amount of risk (no offense to your momma).

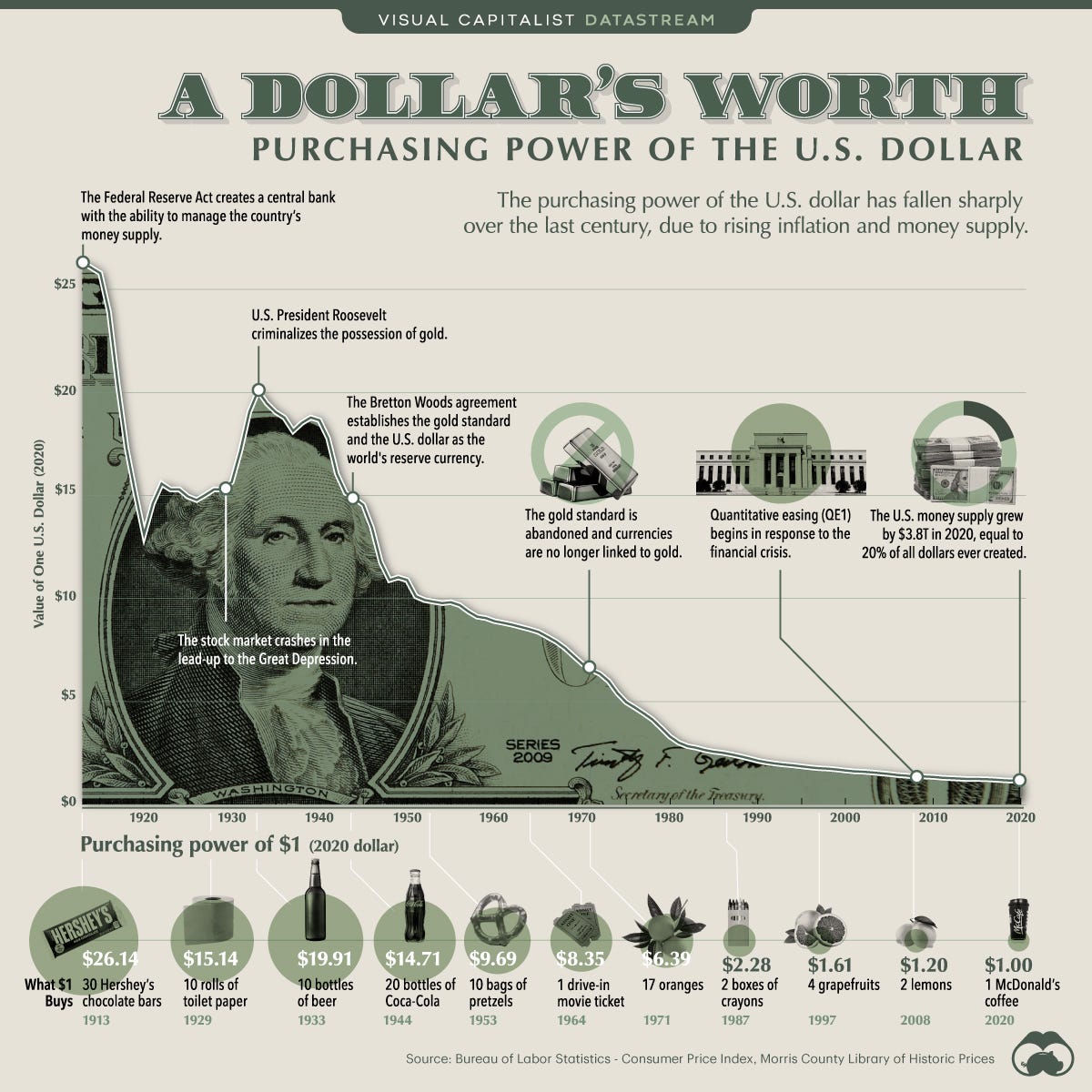

Inflation Premium: This one compensates investors and businesses for the impact inflation will have over the maturity of the investment. It’s important because it accounts for the fact that inflation reduces the purchasing power of a unit of currency. In other words, it reduces the amount of goods and services a dollar can buy. As we have seen, inflation has risen substantially since the Covid-19 pandemic and the purchasing power of the dollar has substantially decreased with time.

Here’s an important side note. Adding the real risk-free rate and the inflation premium give you the nominal risk-free rate. Treasury bills, for example, are the closest proxy to a nominal risk-free rate.

Default Risk Premium: This one compensates for the fact that someone might default on their promise. If someone borrows money (borrower) from someone else (creditor), there’s a chance the borrower might default on that loan. Circumstances like losing a job (in the case of individuals) or losing customers (in the case of businesses) can lead to the inability to repay that loan.

Liquidity Premium: This one covers the risk that someone might need to sell an asset like a stock, bond, or real estate at a discount because there’s not a market that trades these as quickly as possible. An example of this is what happened to mortgage-backed securities in 2008 during the financial crisis.

Maturity Premium: This one compensates investors for the market volatility that interest rates have on debt, especially long-term debt. There’s a lot of investments with different maturities, from a few days with Treasury Bills to 20 years with Treasury Bonds. The difference in interest rates between short term and long term debt comes from a higher maturity premium on longer term debt.

It’s important to note that these premiums are not all included in an interest rate.

Which ones are baked into the interest rate will always depend on the nature of the financial instrument you’re dealing with. Stocks, for example, don’t have a maturity date. Therefore, they won’t have a maturity premium as they don’t expire.

Another important thing is that some interest rates might be fixed and others variable (or floating). I’ll show you why this matters in a second.

Great, so now that we understand all of that … so, what?

How does it actually affect your pockets and those of businesses and corporations?

The Domino Effect

Let’s take a hypothetical example.

Imagine a business — let’s call it Captain Electric — that relies heavily on a line of credit to manage its accounts receivables. They do this because they have long payment cycles and irregular cash flows (quite normal in manufacturing and construction industries).

Let’s say Captain Electric secured this credit line at a floating interest rate of 5%. What this means is that the rate is tied to a benchmark and adjusts with market conditions. A common one is the LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate).

Now, due to rising inflation, the central bank decides to tighten monetary policy, which results in an increase in interest rates (sound familiar?). Captain Electric suddenly finds its interest rate on the line of credit soaring to 10%.

This single decision by the central bank could have a massive impact on business operations for Captain Electric. A domino effect that will be felt throughout the entire company.

Let me illustrate:

Domino 1 : The interest expenses on the line of credit would double, right? From 5% to 10%. If Captain Electric has substantial borrowings, this could mean a significant monthly increase in interest payments.

Domino 2: With more money directed towards interest payments, there’s less money available for research and development, marketing, or even payroll. Cost-cutting begins.

Domino 3: Expansion plans might need to hold off. Inventory purchases might need to be put on pause or reduced, which might become a problem if customers are demanding the product. This will turn out badly from a customer satisfaction standpoint.

Domino 4: If Captain Electric is a publicly-traded company, this will definitely have analysts questioning how/when will they deleverage the company and reduce interest expenses. This will influence the stock price and investor confidence.

Domino 5: Executives start steering the company in a different direction.

Do you see it now? I may be exaggerating a bit on the one above, but not by much.

Interest rates dictate a lot of the behavior consumers and businesses engage in.

I’ve always preached that executives and entrepreneurs should have a good understanding of macro and microeconomic factors.

Because business performance and personal finance are intricately tied to how interest rates move.

Spending a little bit of time understanding this metric will serve you well.

Economics is everywhere, and understanding economics can help you make better decisions and lead a happier life.

Tyler Cowen

I hope this attempt of explaining something so pervasive in our lives is helpful to you and your friends and family.

If you enjoyed the article, please forward it to someone you know to spread the word.

Wish you a fantastic weekend ahead.

Remember to add some spice and variety into your life to keep it interesting.

I’m doing so by enjoying this amazing scorpion taco in Mexico City.

Until next time,

Antonio.